William Knox D’Arcy should be a household name, but is widely unheard of outside of the Petro-chemical industry. He was the only son of an Irish solicitor, and in 1865 his life was literally turned upside down, when his father’s law firm went bankrupt. Due to a combination of embarrassment and debt, the D’Arcy family were obliged to skip town and jumped the boat to Australia. This was the start of a chain of events that would make William a very rich man, help fuel an empire, and give Britain the resources it needed for successes in both the First and Second World War.

William was born in Devon, England on 11 October 1849 and was educated at Westminster School, London, from 1863-65. The following year after their rather hurried journey down under, the family arrived in Rockhampton Queensland. The father, also called William, opened another law firm and young William continued his education and qualified as a solicitor, he got a job working at his fathers’ practice before, eventually setting up on his own. A natural entrepreneur William did quite well speculating in land and gold stocks something that would put him in good stead for the future

The Mount Morgan Gold Mining Company

His interest in mining started in 1882 when three brothers Fred, Edwin and Thomas Morgan applied for a prospecting licence to dig at Ironstone Mountain, some 20 miles south of Rockhampton. With a licence in hand, they proceeded pegging out part of the mountain. ‘Pegging out’ is where you drive pegs or stakes into the ground surrounding the area where you are prospecting for gold, which is where the phrase ‘stake your claim’ comes from.

A small amount of gold was found but the work was slow and they soon ran out of funds. Anxious to carry on, they approached a local bank for more cash. The branch manager not entirely satisfied with their belief that more gold was forthcoming, suggested that they contact local private businessmen like D’Arcy for backing. Ever the entrepreneur D’Arcy jumped at the idea and formed a syndicate with another seven businessmen and together they raised the needed capital.

Worried about the initially low rate of recovery, the Morgan boys sold their interests by October 1883 to the syndicate for approximately £100,000. As time went on more gold was found and profits rose. The biggest problem for the syndicate were the claim jumpers who encroached on their pegged areas and D’Arcy’s legal training was tested fully in the complicated litigation which resulted.

By 1886 gold was being discovered in ever greater quantities, and ‘The Mount Morgan Gold Mining Company’ was established with one million £1 shares. William Knox D’Arcy was one of the eight original shareholders and directors, with 125,000 shares in his own name and 233,000 in trust. At one stage the shares reached £17 1s. each, William became a millionaire.

With his newly found wealth he lived a very comfortable life with his family in the Rockhampton suburbs. He became President of the local rowing club and on the committee of the Rockhampton Jockey Club. But for D'Arcy the problem with Australia was, it didn’t have the class system that was alive in England, where if you had money you were somebody. So, in 1886 he sold his legal practice and moved back to England. He never returned to Australia although he remained a director of the Mount Morgan Gold Mining Co. as chairman of its London board.

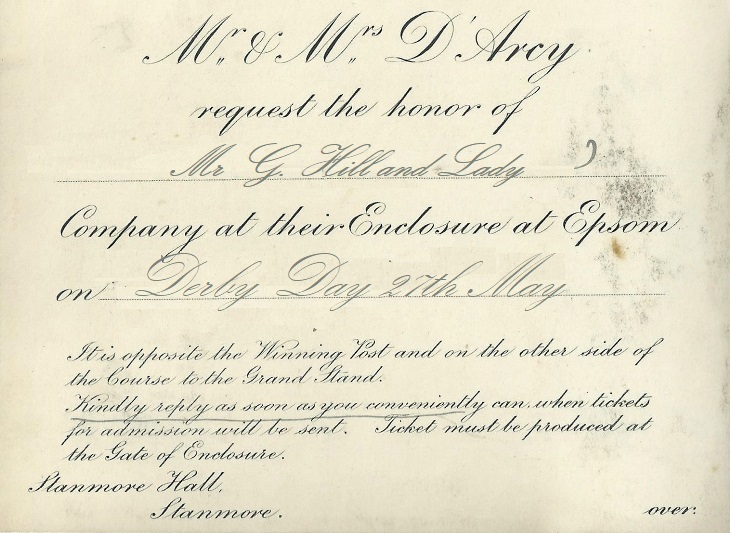

Now back in England, William Knox D'Arcy could really show off his wealth. In 1889, he and his family moved to Stanmore he purchased Stanmore Hall and also a London town house. In Australia two of his biggest passions were shooting and horse racing, so he bought himself a private stand at the Epsom racecourse. During this period there were only two private stands at Epsom, and the other was owned by King Edward VII. William also bought Bylaugh Hall, a country house situated in the village of Bylaugh in Norfolk where he would host shooting parties on his 19,000 acre estate.

William Morris

It was said that D'Arcy's lavish lifestyle emulated the future king Edward VII, and now at Stanmore Hall, William had his own castle. He employed the services of Brightwen Binyon the architect and had the Hall greatly enlarged, the interior decorated like a palace, and the gardens landscaped. He had a fondness for oil paintings and amassed quite a collection including works by Frank Dicksee and Frederick Goodall.

He commissioned from William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones a suite of tapestries; they were on the theme of the 'The Quest of the Holy Grail’. Six in total they were hung in the dining room and each one depicting a different scene from the legend of King Arthur and the quest for the Holy Grail, as told in Sir Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur. Like similar Morris & Co. tapestries, this sequence was a group effort, with overall composition and figures designed by Edward Burne-Jones, heraldry by William Morris, and foreground florals and backgrounds by John Henry Dearle. The tapestries remained at Stanmore Hall until after D'Arcy's death. In 1920 along with many other features of the Hall, they were subsequently sold off and dispersed.

William Morris had strong socialist leanings and although he was happy to take the job and the money he was rather patronising about Stanmore Hall and Brightwen Binyon, writing of them on 10 June 1890 as "a sham Gothic house of 50 years ago now being added to by a young architect of the commercial type men who are very bad. Fancy in one room there was not a pane of glass that opened." He hated the way that the locals would touch their caps as D’Arcy would pass them.

It’s not much good doing all that work and no one seeing it, so happy with the work inside and outside the hall, D’Arcy commissioned the photographer Bedford Lemere in 1892 to document and photograph the property. After Mr D’Arcy’s death in 1917 the album that he produced found its way to Australia, and is now in the possession of the National Gallery of Victoria.

William was living the good life but all play and no work is never a good combination. Things started to go wrong when he lost a huge chunk of his money as the Queensland National Bank declared bankruptcy during the Australian banking crisis of 1893. To add to that the value of his Mount Morgan shares had declined, but the cost of his extravagant lifestyle was still mounting. A new project had to be found and it came in the shape of a new mining venture, and this time it was in oil....

Oil prospecting in Persia

During 1900 D’Arcy was approached by old friend and former British ambassador to Tehran, with regards to a venture in oil exploration. For many years it had been rumoured about a hidden oil field in Persia. D’Arcy agreed to bankroll the project and sent an envoy who obtained a concession to search for oil over 480,000 sq. miles. The sixty-year contract gave D’Arcy exclusive rights to explore, obtain, and market oil, natural gas, asphalt, and ozocerite. In return, D’Arcy agreed to pay the Iranian government ₤20,000 in cash, ₤20,000 in stocks, and sixteen percent of the annual profits.

The dig started in earnest but two years and £150,000 later no oil was found. Running short on funds William was forced to mortgage his Mount Morgan stock, he couldn’t have picked a worse time as they had dropped to about £2.00 a share a far cry from their £17.00 peak. Two years later he had spent some £225,000, a considerable sum in 1905 especially with nothing to show for it. By now things were getting serious for William, overwhelmed by debt he had just sat down for supper one evening, thinking this may be one of his last at Stanmore Hall before the banks foreclosed on him, as a last resort he approached the Rothschild family over the sale of his concession. Word spread and on 20 May 1908 the British owned Burmah Oil Co. stepped in with an offer, backed by the British Government.

D’Arcy agreed to it and drew up a new contract to cover the deal. Now, under this contract, he received 170,000 Burmah Oil shares and a payment to cover all expenses he had incurred so far. He was also allowed to own whatever oil he found in Iran and pay the government just 16% of any profits he made.

Then just six days after he had drawn up the new contract oil was found, but this was no ordinary find, his team had unearthed the biggest oilfield ever discovered in the world. After this first discovery on 26 May 1908, William Knox D’Arcy became sole owner of the entire ocean of oil that lay beneath Iran's soil. No one else was allowed to drill for, refine, extract, or sell Iranian oil.

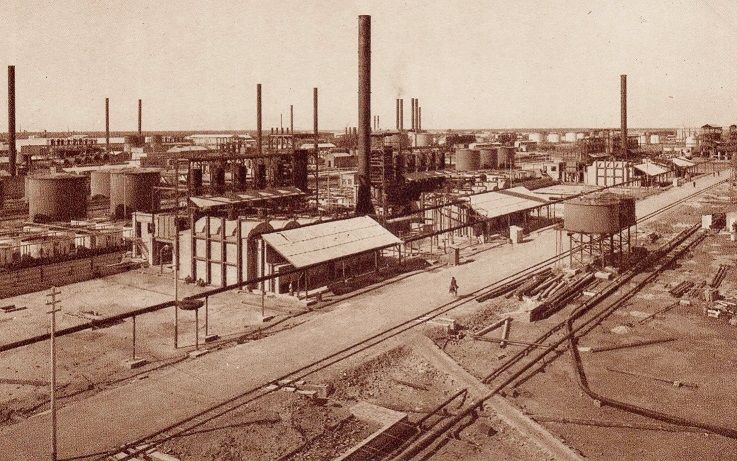

On 14 April 1909, Burmah Oil created a new subsidiary company. The new company would be called The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (AOPC). Production eventually started in 1913 from a refinery built on the port of Abadan on the Persian Gulf. For the first 50 years of its life it became the largest oil refinery in the world. D’Arcy was appointed to the board of the new company, where he remained for the rest of his life.

In 1914 after an act on Parliament the British government got involved and paid £2 million for a 53% stake in the oil field, they brought a new customer on board, Winston Churchill who was at the time First Lord of the Admiralty. The main reason for the intervention of the British government to get involvement in the oil concession was intimately connected with the Navy. The British navy was converting the fuel systems from its ships from coal to oil which were faster and more efficient. A thirty-year contract between the Admiralty and APOC was drawn up, and soon Iran became the first and most important oil producer for the British empire.

Winston Churchill was quoted as saying "Fortune brought us a prize from fairyland beyond our wildest dreams, "Mastery itself was the prize of the venture."

From the 1920s into the 1940s, Britain's standard of living was supported by oil from Iran. British cars, trucks, and buses ran on cheap Iranian oil. Factories throughout Britain were fuelled by oil from Iran. A thirty-year contract between the Admiralty and the company ensured a steady supply of Iranian oil to the Royal Navy at substantially reduced prices, that would go on to influence the direction of both World Wars.

In 1895, his 23-year-long marriage collapsed. Elena, mother of his five children, reckoned all the ‘flattery and success has turned his head' and blamed all the ‘misery and unhappiness’ of her life on Williams wealth.

For William Knox D’Arcy to be seen to be wealthy was more important than the money itself, now better off financially William lived the life he’d always dreamt of. In 1899 just two years after divorcing Elena, D'Arcy married Nina Boucicault, daughter of Irish-Australian newspaper boss Arthur L. Boucicault. Nina was a first cousin of her namesake, Nina Boucicault, the celebrated Irish stage and film actress. She would love to entertain and he loved to spend, often throwing extravagant banquets for their showbiz and society friends at Stanmore Hall and entertaining London society’s most influential at his private enclosure at Epsom. The D’Arcy’s also owned a town house in Grosvenor Square, after one such arrival from Stanmore, the Times newspaper printed that they had arrived there ‘from the country’ and went on to describe Nina as ‘a tall, slim, handsome woman, with an abundance of pale golden hair. She is a good bridge player and a quite exceptionally graceful dancer’.

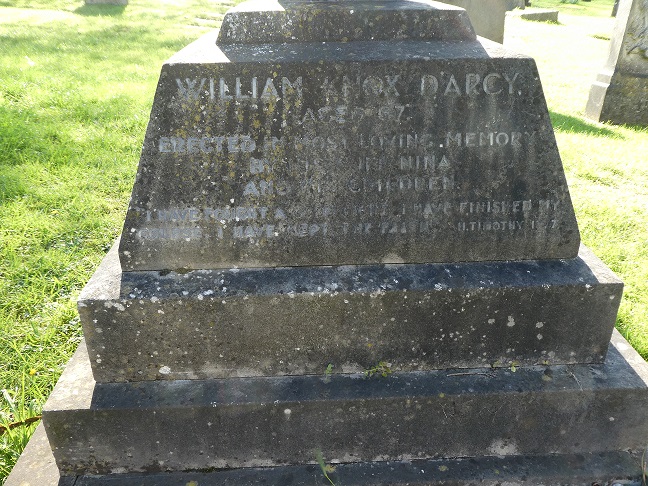

D’Arcy died on 1 May 1917 aged 67 at Stanmore Hall of broncho-pneumonia, survived by his wife and children. His immense service to the British Empire and Persia was, however, never fully recognised. His death was widely reported locally, nationally and internationally, the founder of the oil industry in the Middle East was dead. Dignitaries and celebrities attended his funeral in Stanmore and the route was lined with spectators as the hearse drawn by horses with black plumes slowly carried the coffin through the village on his final journey to the church of St. John the Evangelist for the service.

He was buried on 5 May 1917 in the grounds of St. Johns. The epitaph written on his grave reads:

aged 67.

Erected in most loving memory

by his wife NINA and his children.

" I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept my faith"

n. Timothy IV. 7.

When he died it was estimated his estate to be worth some £984,000 a considerable sum of wealth in 1917. And would be the equivalent of nearly £50 million today.

In 1935 William Knox D’Arcy’s APOC was renamed the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company or (AIOC), after the Iranian government decided to rename the kingdom, and requested those countries which it had diplomatic relations with to call Persia "Iran," which is the name of the country in Persian.

In March 1951 the Iranian parliament voted to nationalise the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and its holdings. In retaliation the British government put pressure on other countries not to buy Iranian oil, the successful boycott known as the ‘Abadan Crisis’ led to the closure of the huge Abadan oil refinery. AIOC withdrew from Iran and increased the output of its other reserves across the Persian Gulf.

In 1954 D'Arcy's company which started life as a small subsidiary of Burmah Oil was renamed The British Petroleum Company. They expanded beyond the Middle East to Alaska and was one of the first companies to strike oil in the North Sea. In 1978 they acquired majority control of Standard Oil of Ohio. They merged with Amoco in 1998, becoming BP Amoco plc. In 2000 they acquired ARCO and their old parent company Burmah Castrol. The following year 2001, they changed their name for the last time becoming what we know today as BP plc.

Professor Geoffrey Blainey the distinguished Australian historian, described D’Arcy as: the most remarkable of all business stories because of his involvement in two such profoundly successful ventures on opposite sides of the world. But more importantly for his role in the discovery of oil in the Middle East and the impact this has had on business and political history to this very day.